Context & Identity in Contemporary Hungarian Art

Reimagining the near past and constructing local identities. A Fulbright project by Linnea West (2012-13)

Essay

Identity and context in contemporary Hungarian art:

(De)constructing local identities and (Re)imagining the near past

My interest in what legacy the unofficial art of the Socialist period—and its critical, socially engaged, and strongly conceptual nature—had left in a newly democratic society I originally defined in terms of national identity, a term few artists I have met with use to describe their own work. The long and complicated history of nationalism in this country, which still is present today, has lent a charged significance to the concept of national identity. Yet the works I focus on encompass a broad and nuanced conception of Hungarian identity, un-bordered by traditional nation-state terms. The works are valuable to examine because they represent the local importance of exploring the nuances of an obscured past as well as an ongoing process of cultural self-definition. At the same time, how artists navigate this relationship suggests not only the complexity of navigating historical consciousness and specifics aspects of history but of operating in an increasingly global art world while instigating discussions of local subjects.

1. INTRODUCTION

This paper presents a selection of contemporary Hungarian art in which the past is very much present, awareness of it mediated, examined, and contested, at times re-imagining with reflexive self-awareness an already mythic past. Within this, anthropological discursive projects uncover local identities, either making visible the margins or critically examining sub-segments of society which alternate between a local or regional view of identity as much as a national one. Overall these artists and in particular the mentioned works form a cohesive group not just in theme but in approach. These projects are thematically characterized by the deconstruction of cultural myths, the treatment of history as a series of pluralistic and possibly false narratives, and the transformation of Communist and older symbology through appropriation and re-contextualization. This post-modern and conceptual approach to art balances the ‘evidence’ of reality with a critical distance, also reflecting an awareness of the artist’s role as mediator of information. It is work characterized by discursiveness, and in which the possible distance between artistic representation and reality embraces an imaginary aspect, perhaps the descendent of the ‘irony as weapon’ of the neo-avant-garde of the 1960s and 1970s.

The first section highlights critical, Conceptual artwork that engages the Hungarian past in ways that allow for a nuanced and pluralized interpretation of national identity beyond a nationalist one. Considering several projects in-depth, historical consciousness rather than history itself is examined—with a focus on how history has been told, what has been ignored, and questioning the systems, influences, and motivations of these processes. Often characterized by a scientific or research-oriented approach, this post-modern sensibility is not unlike the latter process Michel Foucault describes as the ‘intrinsic description of the monument’:

“There was a time when archaeology, as a discipline devoted to silent monuments, inert traces, objects without context, and things left by the past, aspired to the condition of history, and attained meaning only through the restitution of a historical discourse; it might be said, to play on words a little, that in our time history aspires to the condition of archaeology, to the intrinsic description of the monument.” [1]

The use of documentary, or ‘real,’ evidence is counter-acted by a fictional or fanciful addition of the artist, which suggests an awareness of the problems of critical distance in investigations of one’s own culture. This awareness implicates the authors of the works in a complicated personal relationship to their subject matter, whose complexity is not lessened by the continued relevance of historical situations to the present day and the sometime politically motivated nature of the works.

The second section considers the function of context, especially potential problems in the densely contextual role of art based on a complicated history. Context plays a determinate role in the reception of Hungarian artwork related to historical consciousness. This is especially true when the artist’s motivation is to address societal problems. However, the heavily contextual nature of art being made now—echoing the isolation of the Socialist period—limits its audience on an international level and at times even within Hungary. Altogether, historical consciousness itself is considered, and with it the role identities and context play in the creation and reception of such artwork, which creates an expanded if deconstructed notion of national as well as other collective identities.

j

2. IDENTITIES

Collective identities are formed in relation (if not in descent or reaction) to a society’s beliefs about history, something which the following critical, Conceptual projects suggest that contemporary Hungarian art challenges more than it reflects. Historical consciousness operates in them much as Foucault describes history in our time, which:

“… undertook to ‘memorise’ the monuments of the past, transform them into documents, and lend speech to those traces which, in themselves, are often not verbal, or which say in silence something other than what they actually say; in our time, history is that which transforms documents into monuments. In that area where, in the past, history deciphered the traces left by men, it now deploys a mass of elements that have to be grouped, made relevant, placed in relation to one another to form totalities.” [2]

The artists create monuments from ‘documents,’ that is historical or archival material, and ‘traces left by men,’ such as architecture, while suggesting the personal nature of these new ‘totalities.’ The documents of the past are questioned, as are their authors, forms, and relations. In that sense, the investigative aspect of these projects can be called archaeological. Paradoxically the final outcome is as much deconstructed as constructed and as much false as true. Certainly they share a sensibility that they, self-aware as authors, are creating narratives of historical consciousness between empirical evidence (documents, buildings, traces of the past) and personal re-imaginings.

This discursiveness acts to deconstruct formative cultural myths and represent ignored aspects. The permutations of these cultural investigations are varied, and reflect not just Soviet dominance but a longer sweep of historical memory including the glorified Austro-Hungarian Empire and the mythic origins of a great race of warriors. The following seven projects cover a wide range topically but are linked by a discursive approach to historical consciousness. Through each of them, a re-consideration of collective identity emerges. First, József Szolnoki’s Homeopathic Reality exhibition at the Ernst Museum conceptualizes the sweep of Hungarian history in a series of key moments of transition, dissecting the binary categories of Eastern and Western identity with a highly symbolic retelling of history. Relating the first half of the 20th century to the present day, Szabolcs KissPál brings together the history of the Budapest Zoo, the regent of Hungary during the interwar period Miklós Horthy, and the role of Transylvania and Trianon in a docu-fiction project called Amorous Architecture. Gergely László’s The Collective Man project archived and then performed the social reality of a changing community, a kibbutz founded by Hungarians. Andreas Fogarasi presents the cultural centers of Budapest as character witnesses to change in Hungarian society, representing a Communist and post-Communist identity that is regional as much as Hungarian, in his work Kultur und Freizeit. Deserted Memorial, a project displacing a forgotten, defaced plaque of the Communist period, is a project by Little Warsaw that asks questions about the meaning and relevance of artworks that outlive their original eras and the use of public space to tell history.

The final two projects relate particularly to the formation of historical memory. Concerning historical consciousness today and the institutionalization of collective identity, Zsolt Keserue’s National Textbook is a collage book of data about Hungary, its formation and history, gathered from textbooks used in the public education systems of other countries. Csaba Nemes takes another current approach to identity, in his film Remake, that presents the protests and riots of 2006 in a series of short films that ape mass media, documentary, and music video formats. The ideas of collective identity that emerge from such investigations allow for a plurality and complexity in how identity is understood.

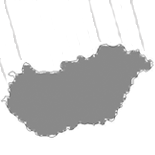

1. Installation view, Homeopathic Reality exhibition, Ernst Museum, Budapest, 2011

The 2011 exhibition Homeopathic Reality at the Ernst Museum-Budapest brought together recent work of József Szolnoki that overall positioned itself as the cure for false historical consciousness with a homeopathic remedy of similarly false doses of memory and history. While Szolnoki draws on his own Catholic and Communist past—and the double identities that evokes—he also goes further: into the whole past of Hungary as a nation. His private mythology reorganizes Hungarian history according to a notion of “transitoriness,” in which a ferry between East and West signifies moments of historical consequences, beginning with the recently discovered dinosaur named Magyarosaurus. However this concept is not motivated by nostalgia or true belief in a mystic reordering of the world, rather it is a tongue-in-cheek commentary on unassuming but defining moments and their legacy.

Szolnoki’s primary medium is video, and the exhibition features films such as 2009 One Time Hun, Always Hun about a segment of German and Hungarians who celebrate their questionable lineal descent from the Huns. While researching a group of Huns in Cologne for a project, Szolnoki became aware that a similar group of Hungarians raised a motion in Parliament asking that the Huns be considered an official minority. From the notion that Huns were aliens to a consideration of archaeological remains and linguistic work, multiple theories and viewpoints about the origin and disappearance of the Huns are brought forward in the film. In an extension of the project, Szolnoki brought a Cologne man convinced of his Hun origins to the Kunsthalle as part of his 2009 exhibition Huniversum. The action involved this shaman Hun from Cologne, dressed in elaborate costume, standing in Hero’s Square in Budapest, where tourists could take pictures with him.

Szolnoki’s method “streamlines” aspects of culture, refashioning elements of tradition he considers possibly, or probably, false.[3] Of the many works on view, examples of the topic and method he uses are his action 162 beer mugs, in memory of the 150-year ban on clinking beer glasses, ineffective for 12 years, 15 September 2011 and The Kádár badge removed from the side façade of Műcsarnok in 1999. The former action involved breaking the Hungarian taboo of clinking beer glasses, whose origin is disputed but thought to relate to resistance to the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, by clinking 162 mugs of beer, one for each year the ban was in effect. The latter puts on display, as the title suggests, a badge of the János Kádár government previously hung on the façade of Budapest’s Kunsthalle, part of a series of works in which Szolnoki displays coat-of-arms of successive governments that have appear on different kind of buildings in Hungary—from cultural institutions to government centers to kindergartens. Instead of being replaced in each successive government change, sometimes the old crest is merely painted over, and at times the paint deteriorates or peels to show the records of the past underneath. Szolnoki collects such painted-over coats-of-arms, considering the physical traces of the past visible in a way he likens to palimpsest. Other objects that bring the traces into view are also part of an ongoing research and archive he is creating including objects such as books or pins. Bringing them together draws attention to them and asks for their reconsideration as objects—the artist suggests it is a psychological tick of society not to be able to see such visible permutations of history.

Complementing the archival approach of the coat-of-arms research, the exhibition featured factual material, collected and arranged. So, The Kádár badge removed from the side façade of Műcsarnok in 1999 was shown with documentary evidence of the building before and after its removal. Overall, “[r]eality as a readymade is both entertaining and thought-provoking; the display, which visitors are invited to discover on a predetermined route, presents in chronological order the stages/works of art that relate to or reinterpret the changes in the east-west orientation of Hungarian history.”[4] This journey that the artist arranges in the exhibition transforms the traditional historical categorization of East and West, beginning in the East with the prehistoric origins of the Hungarian state and ending on the Eastern shore with a question mark.

2 Still from film Amorous Architecture, 2012

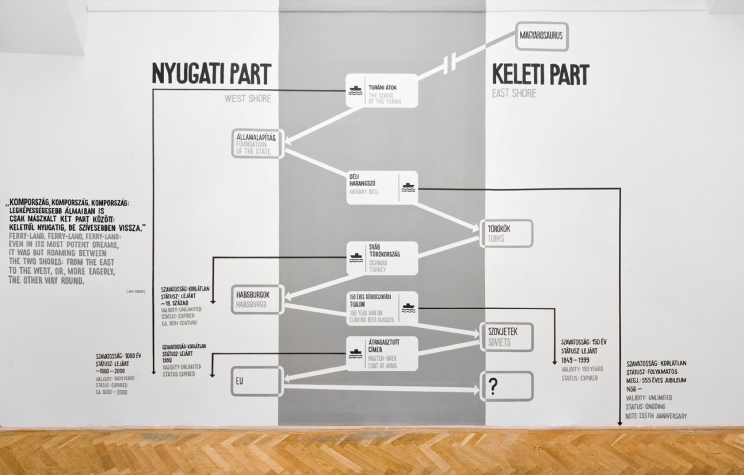

Taking the Budapest Zoo as its initial subject matter, Amorous Architecture by Szabolcs KissPál consists of text and video work made in conjunction with the book-as-exhibition project Zootopia.[5] KissPál is a Budapest-based visual artist who uses different media (often video but also photography, installation, and sculptural objects) in detached, at times critical and at times poetic, examinations of society. While he often looks at themes such as the function of money or nationalism in society, his most recent project, Amorous Architecture, closely considers the documentation and circumstances surrounding the creation of the zoo in Budapest at the turn-of-the-century. Evidently intrigued by the zoo’s still-present artificial mountain, this docu-fiction project explains the circumstances of the mountain’s construction while linking it to nationalism’s darker side of colonialism and the historical tensions surrounding the region of Transylvania.

KissPál begins with factual, documentary evidence that is the result of research; he then twists this research to tell a fictional narrative. The Budapest zoo was built at the beginning of the 20th century, at a time when nationalist pride was often displayed through public architecture. The zoo’s Transylvanian architect introduced typically Transylvanian elements into the design of the zoo, including the artificial mountain built to resemble an actual mountain in Transylvania (rejecting other possible models such at Mount Sinai). Folk elements from Transylvania are often considered quintessentially Hungarian, although the Treaty of Trianon would annex the region to Romania, a continuing wound in the national psyche.

3 Still from film Amorous Architecture featuring archival image of Horthy, 2012

An intertwined element in KissPál’s narrative of the early history of the zoo centers on an archival photograph of Miklós Horthy, then the regent of the Kingdom of Hungary. The image shows Horthy standing in front of a line of kneeling people in traditional Transylvanian costumes in the zoo. The photo dates from a period in which colonialist countries would display indigenous people from their colonies in zoos as an ethnological exposition, a trend KissPál graphs in his film. Keying off of these facts, KissPál, in his video, constructs a narrative about Horthy inspecting live Transylvanians kept on display in the Budapest Zoo. What does it say about the identity of Transylvanians that they are considered typically Hungarian on hand, and on the other are shown as a zoo exhibit like a colonized people? The artist uses this narrative to deconstruct ideas about turn-of-the-century Hungary, the status of Transylvania to Hungary, the role of Horthy as a leader, and the retelling of history.

This dense project has many more allusions and complexities; its name, for example, is borrowed from a popular TV program. It should also be noted that Transylvania, Horthy, and Trianon retain their resonance today within Hungarian societye. One of the challenges KissPál dealt with in making this work is lucidly referencing Hungarian history; for example, it can be unclear to an international audience why the historical topics of Horthy and Transylvania are inflammatory today. A nationalist utopia of the past in a seemingly innocent structure—a zoo—is undercut by a narrative of nationalist tensions that a century later have not disappeared.

4 Photograph from performance of The Collective Man at Witte de With, Rotterdam, 2010

The many iterations of Gergely László’s Collective Man project considers another Hungarian identity outside of Hungary’s borders: that of the Hungarian Jewish kibbutz of Yad Hanna. László’s discursive projects take archival and documentary approaches to bodies of knowledge, typically socio-cultural, in addition to embracing community in his artistic practice. László’s project on Yad Hanna, a kibbutz in Israel founded by Hungarians in the 1950s, explores the different facets of this community from its founding until the present day. His work takes multiple forms: first, in 2008, he went to live on the kibbutz and created an archive. Later, he took this archival material as inspiration for a play The Collective Man, which has been performed at the International Studio and Curatorial Program (ISCP) in New York, in Budapest as part of an exhibition at the Ernst Museum, and at the Witte de With in Rotterdam.[6] The narrative revolves around the history of Israel’s best-known communist kibbutz, whose founders include the younger sister of László’s maternal grandmother as well as her husband.

Over time the community has changed dramatically. Walking through the now-privatized land, László first began documenting changes to the architecture, manifestations of how people build when they are sole owners of a property compared to when they live communally. The population of the kibbutz has changed as well. A few founding members still live there, such as László’s relatives, as do refugees and migrant workers from parts of the world as diverse as Thailand and Sudan. In addition to the photo series that he made, the artist began collecting photos from older members of the community in an unused bunker, asking about the stories behind them. Although it was a family connection that first brought László to the kibbutz, his perspective is not nostalgic. The result is a rich, thematised collection of 1,200 photos he presents as an archive, both in two large metal boxes (which remain at Yad Hanna) and as a keyword-searchable database. The process of building the archives and going through hundreds of photos was how László learned the history of Yad Hanna and communal life, its struggles, failures, and eventual dispersion as children moved away from the lifestyle their parents had created. Personal interest in a larger historical moment is approached with critical distance, as research-oriented as an anthropologist documenting a disappearing tribe—as perhaps it is fair to say he is.

This archive provided the material for another project, a play compressing different aspects and times of Yad Hanna’s history and social life. Inspired by photos of Purim plays in the archives, and all the inventiveness and energy that went into the community’s skits produced for this Jewish holiday, László scripted a play called The Collective Man. The basic structure is a fairy tale, and the general content of the dialogue is indicated but intended to be improvised by the amateur actors. The setting and characters reference selected elements from the archival images, so that they become emblematic of things that were once of pivotal importance. On one hand the orderly archives creates a personal, handmade approach to a vanishing past that speaks to a history made up of a multiplicity of viewpoints and memories; meanwhile the performative nature of the play is kept loose and uncontrolled, an unpredictable group effort. The collective nature of both matches in some sense the spirit of the original community.

One on hand, the story of the community is a story of a Hungarian diaspora even as it is of a Jewish homecoming. While it was no direct intention of László to represent Hungarian-Jewish identity per se, it is interesting to note how his work makes visible—especially through his show at the Ernst Museum in Budapest—a Jewish aspect of Hungarian identity. Through Yad Hanna, he creates a symbolic view into the role of history and a sense of home outside Hungary’s borders and yet Hungarian.

5 Installation View of Kultur und Freizeit, Hungarian Pavilion, Venice Biennale, 2007

László’s photography documenting the changed architecture of the original Communist utopia find a parallel on Hungarian soil in Kultur und Freizeit by Andreas Fogarasi. Kultur und Freizeit, a project investigating the cultural centers of Budapest, is a collection of six films presented at Hungarian Pavilion at the 2007 Venice Biennial. These cultural centers, built in different periods of the last century as a kind of working-class community centers, are featured with the camera lingering over their different architectural styles and, almost as an extension or addendum, alluding to their different socio-cultural fates. Fogarasi is an artist of Hungarian origin who lives and works in Vienna; originally trained as an architect, his work is often concerned with cultural branding and how architecture reflect society.

The short films, ranging from four to eight minutes, were shown in minimalist black cubes that situated the viewer in enclosed environments at eye level with the film. Unfinished plywood backs reflected an awareness of the boxes as architectural/sculptural objects, just as the films reflect a meta-awareness of their presentation as film. The accompanying text, on display in an adjoining room of the pavilion, included the Hungarian pavilion in its descriptions of cultural centers, extending this meta-awareness yet again. The approach of the films tends toward the exploratory rather than the didactic as the buildings are presented without context or linear narrative. At times fragmented text suggests the role of the buildings. No conclusion or editorializing perspective is introduced, yet overall the suggestion is of an interest in the possibilities of space rather than a treatment of these buildings as fully realized historical facts.

Questions raised by the work include ideas about the production and ownership of culture: how this has changed historically, what constitutes culture, how it is disseminated or controlled, and with what attitudes we approach it. Take for example, the Hungarian architecture of the 1960s, generally dismissed as being ugly and Communist, and the cultural centers that one interviewee in the film refers to as “brainwashing machines.” Fogarasi allows for an appreciation of these buildings as well-made examples of Modernist style and a tacit acknowledgment that Modernism does not in itself express political ideology. Similarly, because they were decentralized, these cultural centers, in addition to functioning as disseminators of government ideology, were in some sense autonomous and at times were able to be used for distinctly non-official activities.

Here historical consciousness is investigated through physical traces—the buildings—and contemporary attitudes of disdain toward Modernist architecture can be seen as the product of an association of a formal visual style with a concurrent political regime without any clear intellectual link. This project speaks to a collective identity as both a Communist and post-Communist state, which works on a particularly Hungarian level in this iteration but can be considered part of a regional identity as well. The project won the Venice Biennale’s 2007 Golden Lion, the award given to the best national pavilion.

6 Composite image of the artists, of the 2004 removal

Little Warsaw, a Budapest-based artistic collaboration between András Gálik and Bálint Havas, who attended art school as Hungary was transitioning to democracy in the 1990s, is interested in the collective consciousness of society and the role of the artist, and their work often recontextualizes cultural objects, most famously the bust of Nefertiti.[7] Little Warsaw’s work Deserted Memorial takes a forgotten memorial plaque in the center of Budapest as its starting point. The memorial was originally dedicated to the son of Horthy, who died in the second World War.

Defaced during Socialism for being a remembrance of the former regime but left otherwise unaltered, in 2004 Little Warsaw removed this unnoticed marble plaque from the wall. The artists installed it as a sculptural work in The Hague, where it was placed in a park, opposite the bench of Swiss artist Pavel Althamer.[8] Althamer’s art object became a functional place for the viewer to contemplate the memorial fragment. It had reverted to invisibility when its ideological content had been removed—through defacing—and now taken out of context could be reconsidered afresh. Meanwhile the newly exposed brick became visible again, and functioned as a temporary poster space. This was a temporary installation, after which Little Warsaw returned the memorial and cemented it back into the wall of the building. A temporary plaque was added, announcing a forthcoming permanent plaque. Finally, a large inscribed stone commemorating the original plaque was added–all of this happening over the space of the original defaced monument. Layers of history by way of stone memorials now document this once-forgotten object in its original position.

This complicated history, in which a cultural object in the public space goes through many iterations due to changes in the historical consciousness of society, is emblematic of the history of Hungary, and Little Warsaw display the changing social consciousness in their projects. Deserted Memorial is representative of themes found in many of Little Warsaw’s works, where recontextualization is achieved through dislocation in time and space, such as the similar 2004 project Time and Again. Much as Fogarasi does in his consideration of cultural centers, the situations Little Warsaw produce highlight the changing meaning of cultural objects—often sculpture or public art—over time, as well as question the role of the artist.

7 Installation view of National Textbook, Labor Gallery, 2011

Looking at the creation of historical memory itself, via the institutional structure of grade-level education, Zsolt Keserue attempts to deconstruct what Hungary is—its collective identity—through the words of other nations. Keserue’s on-going project National Textbook creates a montage publication of data about Hungary, its formation and history, from textbooks used in the public education systems of foreign countries. Keserue’s intention is to consider “[t]he at times surprising and contradictory versions of events put next to one another in one publication inspire reflection upon historical memory, revealing the relativity of what is regarded as objective.”[9] The final product will be a collage artist’s book. The project is ongoing because of the long process of getting textbooks from across the world and finding translators for the Hungarian sections.

The first presentation of the project, in March 2011 as part of the Gallery by Night series at Studio Gallery, introduced collections of texts based mainly on the textbooks of neighboring countries. Last year, through tranzit.hu’s Art in Schools program, Keserue launched a second part of the project in a local Budapest high school. He worked with the students in a history class to both deconstruct some of the foreign texts he had received and, as a new part of the project, the students asked foreign friends and acquaintances what they thought about Hungary. The stereotypes they collected and pooled together as a complimentary part of the project, which they displayed across from Keserue’s textbook display during a 4-day workshop/seminar/gallery show. This was instructive for the students, underscoring Keserue’s original intention of presenting the many biases within histories, so that Hungarians can consider how history is told, taught, and institutionalized as well as consider their own history from a different perspective. Especially relevant are textbooks from neighboring countries, where a shared history of shifting borders and political control can be presented from an alternative viewpoint. Although motivated by the current political situation, Keserue never inserts his own viewpoint into the project. Through its montage nature, it merely calls attention to the structures that institutionalize our knowledge of the world, asking that history be considered from many viewpoints.

This is an empirically based research project using textbooks to create his own final book, but Keserue most often works with film. Again, his approach is often a documentary one—taking real evidence, as it were. In his 2008 documentary Blast Furnace, he tells the story of cultural life in Dunaujvaros, a city founded in the 1950s to be a model Socialist industrial city. He interviews people who were active in the culture scene from its initial founding, and pieces together their different stories with archival photos and film including present day footage. The approach to history is a lived, personal one that includes the biased accounts of many players of different generations. Keserue’s film Blast Furnace shares Fogarasi’s concerns with the material forms of modernism and the utopia of communism in this documentary.

8 Left, still from video documentation of stolen tank; Right, still from Csaba Nemes’s 2007 video Remake

If Keserue’s work brings us into the present day, Csaba Nemes’s speaks to current ideas of national identity and nationalism in Hungary. The films of Nemes—less so his more personal paintings—deal directly with social themes such as the Roma in Hungarian society, current politics, and recent history. Perhaps Nemes’s most ambitious film was Remake, a 2007 animated film that used or imitated common mass media elements such as TV news broadcasts and music videos. In ten chapters, each with distinctly different aesthetics, Nemes retold or reimagined Hungary’s 2006 protests against the Socialist government of that time, the first sustained protests in Hungary since 1989. Nemes was shocked as peaceful demonstrations turned into riots. His critical examination in this series of short videos tells a quasi-documentary story of events, at times with a distinctly Hungarian twist (for example a song about Túró Rudi, a quintessentially Hungarian candy bar). While the Túró Rudi music is fanciful, the video of an old Soviet tank coming to life and charging through a crowd directly relates to media footage of actual events, so there is a mix of real and unreal in the work. Considering the 2006 protests the first time a new voice—that of the far-right wing—made itself heard in mainstream discourse, Nemes sought to confront the audience with difficult questions.

Other videos in Nemes’s oeuvre pose social issues as artistic narratives, but with quite a clear point, underlining individual social dynamics behind larger movements.[10] A connection between far-right political support and romantic nationalism is evidenced in Softies. The 2009 film opens with actors interviewing a boy in a realistic fashion, so that the viewer at first might think it is a documentary. As the film continues, we switch into a depiction of the story of the interviewee, who it turns out is one of two young men dressing up in betyár (a traditional Hungarian highwaymen figure) costumes and terrorizing a more liberal fellow student. The kernel of truth comes from an internet video that surfaced a few years ago, showing a young man being bullied by two fellow students dressed as betyárs. Again there is a tension between fact and fiction, both in how the work is presented to the viewer and in the content. A certain nationalism motivates this repurposing of the historical betyár figure to suit two young vandals purposes, which in the film are vaguely ideologically motivated. Both in terms of mimicking documentary or TV media aesthetics in his films and in working from found media imagery, Nemes manipulates the evidence and presentation of real life to suit his own purposes. Especially with Remake, one can also wonder what question it poses about the role of media in the 2006 protests, and in history-making and the perception of historical events in general.

József Szolnoki’s Homeopathic Reality, Szabolcs KissPál’s Amorous Architecture, Gergely László’s Collective Man, Andreas Fogarasi’s Kultur und Freizeit, Little Warsaw’s Deserted Memorial, Zsolt Keserue’s National Textbook, and Csaba Nemes’s Remake can be linked in their quasi-documentary, quasi-imaginative investigations of a historical past that never loses sight of the limitations and singularity of their unique vision. These projects display and deploy historical consciousness in a self-conscious way. They question how and why we view the past the way we do. They speak to a plurality and inclusiveness of identities: overall these varied additions and deconstructions of what is means to be Hungarian enlarge a greater understanding of how one can be Hungarian. This occurs, for example, through making visible the marginalized narrative of Jewish-Hungarians or deconstructing the origins and realities of Transylvania as being inherently or typically Hungarian.

By visualizing and presenting alternative narratives, be they factual investigations of the traces of the past or personal reimaginings, these works enlarge not only the idea of national identity (i.e. including non-traditional ideas of what is means to be Hungarian) but the idea of collective identities as such (i.e. that there have been multiple identities—Transylvanian-Hungarian, Jewish-Hungarian, Communist-Hungarian, or even Catholic-Communist-Hungarian). They do so through post-modern strategies of decentralization and questioning. These anthropological, or archaeological, endeavors highlight the nature and systems of history without being didactic or reductive. Here the function of identity is internal in the sense that it exists within the framework of the works themselves. If these projects illustrate the function of identity in historical consciousness, then the next three projects illustrate the role that context plays in the reception of such works, that is, their external function and effects.

j

3. CONTEXT

Art historian Edit András has written persuasively about contemporary Hungarian society being in a state of “collective amnesia” in regards to the past.[11] The idea is part of widespread cultural trauma theory proposed by so many theorists about the former Eastern Bloc—that is, that the many societal transformations from wars to government systems were experienced as multiple, rapid breaks rather than gradual transitions and this caused societal trauma, which today impact attitudes toward the past and collective identity.[12] András argues that artists, and society, were unable to cope with the trauma of the past, as an explanation for the silence:

“As an aftermath of the inability to carry through the “trauma process,” the culture of the Socialist past became a taboo issue. Leaving the past as it is, and not bothering it with excavations and analyses, became a kind of unwritten agreement. In the region, and surely in Hungary, only a few young artists felt it necessary to analyze the past in the shadow of a new kind of globalization and of a new political formation, the deeply desired integration into the European Union.”[13]

Perhaps that explains why, despite the strong history of socially engaged art and major political changes of the preceding years, in 1994, art historian András Zwickl wrote that “issue-based art has not yet become a significant part of Hungarian art. …[T]he attitude of social criticism manifest during earlier decades, in overt or hidden forms, is also missing.”[14] Hungarian art world was eager to join the international art scene after 1989 and current local issues and recent history was not commonly analyzed in contemporary visual art.

Recently, however, the Hungarian visual art scene engages in social issues related not only to the present but to the past; other efforts framed in terms of national identity include the large exhibition this year entitled Mi a Magyar? (What is Hungarian?) at Budapest’s Kunsthalle and the upcoming two-year-long project called ‘Private Nationalisms’ spearheaded by the Approach Art Association in Pécs.[15] Certainly all the projects mentioned in the first section of this paper display a tendency to deal with the past that was notably absent before. They attempt to process in a critical yet engaged manner a particularly Hungarian heritage, but how do they operate externally? If artists are motivated by a desire to reconcile with an obscured past or in some way address the societal trauma of history, it becomes important to judge how effectively they communicate with the viewer, especially on topics which are often complex and to which people have preconceived attitudes.

The historical context of the subject matter becomes a definitive aspect of how the work is experienced. Today, art historian János Sugar argues that the contemporary art of the region is much less context-bound than it was once:

“Maybe the single most important thing that changed in Eastern and Central European art after the fall of Communism is that contemporary art became less context-bound. Previously there was a very repressive social organisation, a manipulated public life and censorship, and because of this the general public lost its trust in official forums and learned how to read between the lines, how to take the context of repression into consideration. This formed a strong social organisation rooted in a kind of social solidarity, but now this is over. Recent works can be understood with greater ease, with less attention, because they are less context-based, more viewer-friendly, and one doesn’t have to know the whole troublesome history of a ‘complicated’ country to decipher an art piece.”[16]

His 2006 statement suggests that artists now work seamlessly between local and international levels without the burden of a ‘troublesome’ history. In fact, contemporary conceptual Hungarian visual art exhibits a notable engagement with the local past, with the twofold result that the work is, on one hand, enriched by a complex history and, on the other, less intelligible to the outside world.

To illustrate the dynamics of context in operation, I consider three projects revolving around the unexplored history of unofficial art in Communist Hungary that navigate this tension. First, I will compare and contrast recent projects by Little Warsaw and Andreas Fogarasi that revive the internationally unknown figure of Hungarian artist János Major, questioning how context can act as a limiting factor internationally. Then I consider a project of Little Warsaw’s that recontextualizes a 1974 performance of Hungarian artist Tamás Szentjóby, showing how context in both works can also limit audience engagement within Hungary.

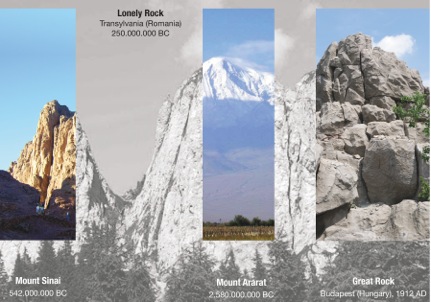

9 Detail of Crew Expendable installation at Ludwig Museum, 2007

Little Warsaw showed an interest in exploring the identity and history of the region before many of their peers, who were more interested in embracing Europe and the West, and similarly they anticipated a local interest in the internationally unknown figure of János Major, a Hungarian graphic and conceptual artist born in 1934 who died in 2008. In 2007, Little Warsaw revived the work of Major in the installation Crew Expendable at the Ludwig Museum-Budapest; notably, since little art historical wok has been done on him and very few of his artworks survive. Crew Expendable was an installation of photography, text, and neon lights. The title was considered provocative, as it presumably references the fate of the Jewish people in particular Major—in whose work his Jewish identity played a prominent role—as those that historically have been considered ‘expendable.’ The neon light work intersects a Jewish six-pointed star with a five-pointed star, from which the word ‘major’ hangs. Is it referencing the major star of a constellation, or the Jewish artist? In fact, it is a signature of the Major used in his prints, in which he himself overlapped a Soviet and Jewish identity through these two stars symbols—two identities that in the governing ideology of the time fit together uneasily at best. Little Warsaw also displayed photographs, snapshot-style, of tombstones in graveyards, from reenactments of Major’s own cemetery walks and photography in the 1970s, which Little Warsaw views as “semiotic.”[17]

In highlighting Major’s work, Little Warsaw anticipated a wider interest now shared among Hungarian art professionals. [18] Major is considered one of the most original and defining artists of the Hungarian avant-garde; he is also one of the most difficult to place. One reason his work remains little known it that the visual art of Communist Hungary, if it was not officially supported by the state, typically did not have the benefit of proper documentation much less the opportunity to be exhibited. This creates a vacuum in Hungarian art history. In addition, the repressive structure of Communism limited the reach of unofficial visual art to a closed circle of art practitioners who created a rich, insular environment of signs. Many layers of historical meaning, political constraints, and other forms of local context made the underground strain of avant-garde art in Communist Hungary all but indecipherable to the outside world. Little Warsaw’s work fits into a larger picture of Hungarian artists and art historians trying to create a nuanced and inclusive view of the visual arts of that era.

10 Still from Vasarely Go Home, 2011

Channeling Major himself and echoing his work is an integral part of Crew Expendable, whereas Andreas Fogarasi’s Vasarely Go Home uses Major as a pivotal character within the overall context of Communist cultural politics. In the 2011 documentary film, Fogarasi traces a double event that took place on Saturday, October 18, 1969. One is that Victor Vasarely had a large retrospective art exhibition at the Kunsthalle in Budapest. The other is a mythical, undocumented action—in which Major staged a discreet one-person protest at the opening of the exhibition. Fogarasi’s entry point into the subject of the film was a fascination with artist Victor Vasarely, a Hungarian exile who settled in Paris and became noted for the popularization of Op Art, a dynamic fashion as well as artistic trend in the 1960s. As a renowned international artist from Hungary, Vasarely was invited to do a show at Budapest’s Kunsthalle in 1969 despite Op Art not being a style supported by the Socialist government. At the opening, Major showed acquaintances a small sign or protest board in his pocket reading “Vasarely Go Home,” an action that became the stuff of legends in the unofficial avant-garde Budapest art circle of the time. Fogarasi asks “Could a western artist understand how little this gesture had to do with envy, aggression or a thirst for professional success, that it was dictated rather by loyalty and self-irony?”[19]

The question could be asked of a Western audience today, but indeed Fogarasi’s project is conceived for an international audience and attempts to create such an understanding. Fogarasi reconstructs the event and its context through interviews with important personages of the Budapest art world of that time. The response to this double event testifies to inclusion and exclusion, West and East, politics and culture, and the making of art history in the region, showing as it does the intersection of two radically different artistic forces—something which Major acknowledged in his action. While Kultur und Freizeit (discussed previously) and Vasarely Go Home both explore Hungary’s specific cultural heritage, the artist’s interest lies in a more universal representation of cultural and architectural space. His treatment of these subjects suggests they are representative of larger cultural trends that relate to the general concerns of his work. The way both operate internationally—a Golden Lion for Kultur und Freizeit, the Reina Sofia’s support for a ‘local Hungarian’ topic—suggest that he is able to translate a specific local context into international terms successfully.

Fogarasi’s film places the figure of Janos Major in a more accessible relation to those who are unfamiliar with the artist than Little Warsaw’s installation. Vasarely Go Home has multiple points of interest and intersection with the outside world that contextualize the figure of Major, whereas Little Warsaw’s installation is enhanced by –or indeed presumes—some knowledge. Little Warsaw’s more ambiguous subjective matter and referential works trade on insider knowledge and make no parallels to the outside world except a confusing title that references a series of blockbuster Alien films. However, one could argue that in focusing on the particulars of Major’s oeuvre, the project by Little Warsaw does Major’s work a greater justice than this film in which he is a central yet unexamined figure who becomes emblematic of larger cultural forces at work. If here we see context working in two different ways, either to enhance an understanding of the role Major had in a larger art world for a general audience or to detailed appreciation of his work for those already familiar with the Hungarian neo-avant-garde of the 1960s and 1970s, next let us look at a second project of Little Warsaw that again tackles a specific, local, and not widely known work from Hungarian art history.

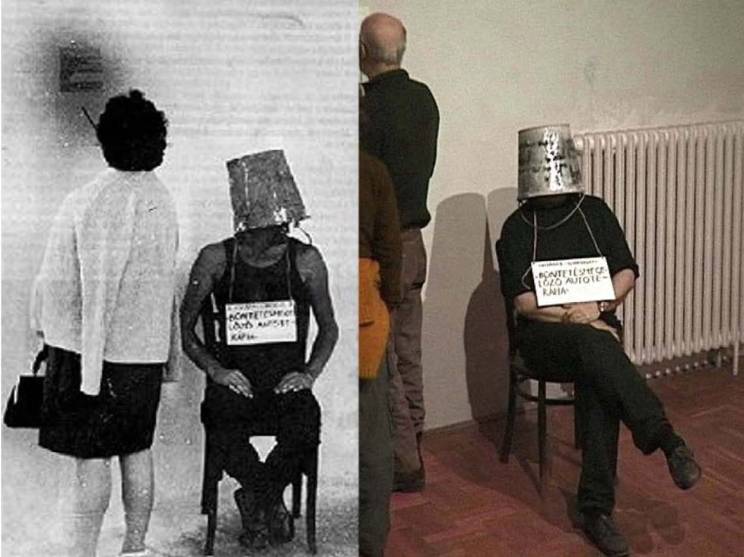

11 Left, exhibition photo of 1972 performance Expulsion-Exercise-Punishment-Preventive Autotherapy; Right, exhibition photo of 2005 Reconstruction – Isolation Exercise – Cyrill & Method.

The 2005 performance Reconstruction – Isolation Exercise – Cyrill & Method by Little Warsaw suggests an interest in (art) historical excavations unconcerned with audience reception, and indeed embracing a covert aspect. Little Warsaw asked Tamás Szentjóby, a Hungarian conceptual artist of the older generation, to repeat a 1972 performance considered “legendary” by the artists.[20] This reenactment was the first in Little Warsaw’s ‘Tableau Vivant’ series; this project aimed to revive artworks of the 1960s and 1970s. In this way, they hoped to examine how reconstructing the works in a new context would create a new perception of artworks of the past. Thus over 30 years after his original performance, Szentjóby performed Expulsion-Exercise-Punishment-Preventive Autotherapy in Little Warsaw’s studio. Little Warsaw documented the new performance in a two-minute video in which one can see the now-older artist sitting, with a similar sign, bucket, and wall text as the original performance, while people crowd around the artist, speaking to him, reading the wall text, or talking in the background. [21]

This performance closely mirrored the original performance of Expulsion-Exercise-Punishment-Preventive Autotherapy in 1972. Sitting with a metal pail over his head, Szentjóby hung a sign around his neck, appearing like a sentenced criminal or a child being punished. He did this eight hours a day for a week. Next to his chair, the wall text read in part:

“I. You can ask anything from the self-sentenced

and

II. You can ask the following:

[…]

–Is there punishment in your action?

– Is there action your punishment?

– Is action a sin? Is punishment a sin?

– Is sin action?

– Is action punishment?”[22]

The philosophical text is typical of the artist, as was its focus on autonomy and ethics, which could be understood as a social criticism. Szentjóby was an active agent of Fluxus and Actionism at this time, integral to introducing these movements to Hungary, and this piece was part of that dissemination.

Szentjóby is uniquely influential on his own and on the younger generation of contemporary Hungarian artists, holding a lionized place in Hungarian art history, a status that has not easily translated outside of Hungary. This is because his importance as an artist and the strength of his work relies on a nuanced understanding of the context it was born out of and reacting to, especially as the backbone of his conceptual art practice is a political and social critique. The ‘great generation’ of unofficial artists quickly became codified in new art historical attempts as institutions presented previously invisible aspects of art history. Szentjóby himself was an early pioneer of such art historical revisionism.[23] Given the historical importance of the original performance, it is perhaps not surprising that Little Warsaw asked Szentjóby to re-perform his action, yet it also reflects a curiosity toward, and a desire to integrate with, an obscured past.

Little Warsaw’s audience parallels that of the original performance. Knowledge of Szentjóby’s 1972 performance existed within Hungary to a limited and closed circle, gaining nuance and meaning through the secretive context. It was performed at Balatonboglar, outside of Budapest, the traditional and extant center of the art scene, and outside any institutional framework. Balatonboglar, a Roman Catholic chapel no longer in use, was an important hub of Fluxus art in this period. Only those who knew it was being used for avant-garde exhibitions would come, and this could not be a widely publicized given the circumstances.

The re-performance in 2005 was held in Little Warsaw’s studio in Budapest, which, while not an institutional framework, is certainly a legitimate art space. But while Szentjóby was limited in his context by political structures, Little Warsaw chose to make a work that operates on a highly local level when it is no longer necessary. To continue the parallel, Reconstruction – Isolation Exercise – Cyrill & Method requires prior knowledge or explanation of the original performance before one can begin to consider the artists’s stated intent: how the re-performance changes the meaning. Even within Hungary, that knowledge is limited to a small group of arts professionals, artists, and intellectuals. Those knowledgeable of Hungarian conceptual art still form a relatively small group of arts professionals, artists, and intellectuals within the country.

The 2005 performance piece demonstrates that the heavily contextual nature of Hungarian visual arts has not disappeared along with “the previous strong, censorship generated attention on art production” that once produced it; rather, this example shows how Szentjóby’s critical conceptual art remains an important reference point for the current generation of artist.[24] The strength of Little Warsaw’s reconstruction is its awareness of this tension and difficulty, even if through a loaded reference dependent on local context rather than emancipated from it. The meaning of this work changes not just because time has passed, but because the context of the artists presenting the work is now an international one, not limited by political structures to an internal circle in a closed country. If the previous comparison suggests different methods for navigating the same tension in Fogarasi’s and Little Warsaw’s approaches, perhaps the reperformance of Szentjóby offers an evocative suggestion of the appeal of such internally focused work that remains rooted in context.

Success in such work is dependent on how effectively these examinations of the past, in this case the art historical past of Communist Hungary, communicate with the viewer. Context in contemporary Hungarian art can exclude not just an international viewer, but anyone outside of insular arts scene, very much in keeping with the tradition of the critical, Conceptual avant-garde of the 1960s and 1970s that preceded it. These three projects specifically deal with Hungarian art history of the Soviet period, but all of the works discussed in this paper engage in Hungarian history to a level of nuance that might limit their audience. Despite János Sugar’s claim, the end of Socialism has not brought the end of insular, context-rich art, even as the audience for it no longer has the same limits. In fact, it is quite the opposite. Hungarian artists today navigate the challenge of exploring their historical and art historical local heritage while feeling increased economic pressure if not also social or personal interest in a broader, international context.

j

4. CONCLUSION

In considering projects such as these—critical, Conceptual works engaged with historical consciousness—in contemporary Hungarian art, the roles of context and identity are paramount. The projects of the first section (József Szolnoki’s Homeopathic Reality, Szabolcs KissPál’s Amorous Architecture, Gergely László’s Collective Man, Andreas Fogarasi’s Kultur und Freizeit, Little Warsaw’s Deserted Memorial, Zsolt Keserue’s National Textbook, and Csaba Nemes’s Remake) show the artist’s active role in (de)constructing local identities and (re)imagining the near past. Identities are treated to a discursive, research-oriented process, even while the final project reimagines the past in a manner that includes fiction or a playful use of historical material. This deconstruction, overall of a traditional nationalist view of collective identity in some form, is conversely a construction of a simultaneous alternative identity. Similarly, reimaging the past suggests that our understanding of it is already an imagined one. In the process of creating an expanded if deconstructed notion of national as well as other collective identities, historical consciousness itself is considered.

Much of the strength of such works is in their rich, nuanced consideration of a complicated past. However, this context can act as a limiting force in the reception of such work, especially but not only, internationally. Can this be viewed as a continuation of the insular nature of the Hungarian neo-avant-garde, which remains highly influential in Hungary even while it is relatively unknown outside of Hungary, further distancing the work from the understanding of an international audience? Or is it the inherent challenges of cultural transmission at work? Representing complex issues of the historical past is a complicated task in itself, and perhaps especially if simultaneously questioning the nature of its own representation. However, it becomes more complicated if the viewer doesn’t have the knowledge to fully understand the work. Many artists in Hungary today seek to operate in (and feel financial pressure to operate in) an international context, reflecting a larger globalizing trend in the art world over the past twenty years and the demands of the art market. While obviously potentially problematic for an international audience, context can also limit the reception of work within Hungary from society as a whole to other artists and art professionals.

This creates a source of friction with the cultural trauma theory, which, when applied to the visual arts, suggests a motivation in uncovering the past and reconsidering truths that will somehow bring to light these issues in the public consciousness. Thus, for artists who are in some sense motivated by this notion of cultural trauma, or set free by it to finally address or reconcile with longstanding societal issues, context is also problematic. In this sense, the weight of context can be as heavy a burden as history itself. These efforts of deconstruction and reimagining seek to carefully consider these workings of history, and perhaps they suggest that after such excavation and examination the loaded symbology and narratives of the past can then be discarded.

Footnotes

[1] Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge. Trans. A.M. Sheridan Smith (New York: Pantheon Books, 1972), 7.

[2] Ibid.

[3] József Készman, “Therapeutic National Theme Park,” Szolnoki József: Homeopathic Reality (Budapest: Ernst Museum, 2011).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Zoo-topia, edited by Eszter Steierhoffer, is a book-as-exhibition publication featuring essays on the architectural and cultural history of zoological gardens and a set of artists’ contributions. More information available at www.zoo-topia.com.

[6] The Collective Man has been performed in April 2010 at ISCP New York; on June 18, 2010 at the Witte de With, Rotterdam; and on December 1, 2010 at the Ernst Museum Budapest.

[7] Little Warsaw’s project The Body of Nefertiti ‘reunited’ the head of Nefertiti with a newly made body at the Hungarian pavilion of the 2003 Venice Biennial.

[8] The installation Deserted Memorial in The Hague consisted of the unification of a contemporary artwork (a removed object from the Kröllermüller Collection, specifically, Pawel Althamer’s 16 Benches) and a memorial fragment (a removed object from the public space of Budapest).

[9] Zsolt Keserue, Website, http://keserue.hu/index0.html (accessed May 5, 2013).

[10] Two other films of Csaba Nemes are worth mentioning in a discussion of identity: Stand Here and George’s Settlement deal with the Roma people in Hungary and how they relate to society. Stand Here (2010) is a puppet animation of an encounter between a woodsman and a gypsy. The woodsman accuses the gypsy puppet of stealing firewood, and the film ends on a somber coda when the gypsy puppet sings to the forest; George’s Settlement (2011) is an animated ‘interview’ of an old coal miner speaking about the decline of the coal mines in Pecs and how it affected relations with the local Roma population.

[11] See “The Unavoidable Question of Nationalism,” Springerin online, 2010, No. 3 (http://www.springerin.at/dyn/heft_text.php?textid=2368&lang=en) and “Transgressing Boundaries (Even those marked out by predecessors) in New Genre Conceptual Art” in Art after Conceptual Art, ed. Alexander Alberro and Sabeth Buchmann (Vienna, Austria: Generali Foundation, 2006) in addition to “An Agent That Is Still at Work” listed below.

[12] Notably Jeffrey C. Alexander and, regarding the post-Communist countries, Piotr Sztompka. See their book Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004).

[13] Edit András, “An Agent That Is Still at Work: The Trauma of Collective Memory of the Socialist Past,” Writing Central European Art History (http://www.erstestiftung.org/patterns-travelling/content/imgs_h/Reader.pdf), 12.

[14] András Zwickl, “Five Years,” in SCAA Bulletin 1991-1994 (Budapest: Soros Center for Contemporary Arts, 1994), 21.

[15] The Mi a Magyar exhibition was held from August 2-October 14, 2013 at the Műcsarnok —Kunsthalle Budapest. The upcoming series of events that is “Private Nationalism,” beginning in Fall 2013, will approach the topic of nationalism from a unique Central European perspective with the tools of contemporary fine arts and its reactive-critical attitude towards societal-cultural processes and conflicts.

[16] János Sugar, “Schrodinger’s Cat in the Art World,” East Art Map: Contemporary Art and Eastern Europe, Ed. IRWIN (London: Afterall Book, 2006), 210.

[17] Little Warsaw, Portfolio, http://www.littlewarsaw.com/Little_Warsaw_Portfolio.pdf (accessed March 25, 2013).

[18] The recent interest in János Major’s artwork is suggested by two exhibitions in 2013, Taboo Subject at tranzit.hu’s Budapest gallery and Leading the Dead– The World of János Major at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts, Budapest.

[19] Andreas Fogarasi, Vasarely Go Home website, http://vasarelygohome.museoreinasofia.es (accessed March 20, 2013).

[20] Little Warsaw, Portfolio, http://www.littlewarsaw.com/Little_Warsaw_Portfolio.pdf (accessed March 25, 2013).

[21] View video documentation of Little Warsaw’s reperformance here: http://youtu.be/FzUKmwbEqIU.

[22] The full exhibition text of Szentjóby’s 1972 action can be found on Exhibition History Blog here: http://exhibition-history.blog.hu/1972/07/06/text_exhibited_with_the_action.

[23] Szentjóby’s Portable Intelligence Increase Museum, a project he began working on in the 1980s, played an important role in the recovery and organization of records of 1960s avant-garde art made in Hungary. Its intent was to be the true record of the “Pop Art, Conceptual Art and Actionism in Hungary during the ‘60s” according to the project’s subtitle. 1,000 plus pieces make up this important collection, part of which has since been exhibited. The merging of research and artistic expression to re-represent the past is a forerunner of the art discussed here. Notably, also, Szentjóby is one of the people interviewed in Fogarasi’s film Vasarely Go Home.

[24] Sugar, “Schrodinger’s Cat in the Art World,” East Art Map, 212.

Bibliography

Alexander, Jeffrey C., Ed. Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

András, Edit. “An Agent That Is Still at Work: The Trauma of Collective Memory of the Socialist Past,” Writing Central European Art History, www.erstestiftung.org/patterns-travelling/content/imgs_h/Reader.pdf (accessed April 20, 2013).

Fogarasi, Andreas, with Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia. Vasarely Go Home website. http://vasarelygohome.museoreinasofia.es (accessed March 20, 2013).

Foucault, Michel. The Archaeology of Knowledge. Trans. A.M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Pantheon Books, 1972.

Keserue, Zsolt. Website, http://keserue.hu/index0.html (accessed May 5, 2013).

Készman, József. “Therapeutic National Theme Park,” Szolnoki József: Homeopathic Reality. Budapest: Ernst Museum, 2011.

Little Warsaw. Portfolio. http://www.littlewarsaw.com/Little_Warsaw_Portfolio.pdf (accessed March 25, 2013).

Sugar, János. “Schrodinger’s Cat in the Art World,” East Art Map: Contemporary Art and Eastern Europe. Ed. IRWIN. London: Afterall Book, 2006.

Szentjóby, Tamás. Text of Expulsion-Exercise-Punishment-Preventive Autotherapy, 1972. Exhibition History Blog, http://exhibition-history.blog.hu/1972/07/06/text_exhibited_with_the_action (accessed April 10, 2013).

Zwickl, András. “Five Years,” SCAA Bulletin 1991-1994. Budapest: Soros Center for Contemporary Arts, 1994.

Pingback: Lecture Tonight in Budapest | Linnea West